In the wake of the controversy over public comments made recently by MPs - namely Diane Abbott’s letter in the Guardian newspaper and the comments made by Miriam Cates at the National Conservatism conference (the focus of this piece, but hardly an exhaustive list) - we wanted to unpack these episodes and see what learning opportunities could be gleaned from these painful situations, with empathy at the forefront. This second piece is from our Founder & Executive Director Sharon, and the accompanying first piece is from our Trustee Zahara. You can read that first piece here.

When I first read the story about Abbott’s comments, I felt both grieved and frustrated. Grieved because of how I know this will hurt people, and frustrated because of the progress that still needs to be made in our national discussion around racism and equality. However, Abbott is not the only MP causing hurt by her comments. Around the same time, Miriam Cates, this time from the Conservative Party, used a term associated with antisemitism in a conference speech.

I think Miriam Cates made these comments coming from her own particular echo chamber of views about the political left, and an ignorance of the historical context of the term ‘cultural Marxism’ with its offensiveness to Jewish people, who were the targets of discrimination and genocide when this term was originally used. Abbott’s context, on the other hand, is one of growing up and then living in adulthood with the weight of the historical crime of slavery and then anti-black racism and stereotypes that have persisted into modern times. For her, it seems likely that these experiences would inevitably become personal considering the terrible racism she has received (particularly on social media), and thus loom larger in her consciousness than others’ narratives. I get the sense that she speaks from a sense of direct victimhood and all the emotions that come with that, resulting in a hurtful and inappropriate ‘ranking’ system of suffering. Thus, both politicians have their vision blurred either by their own experiences of racism, or their failure to understand the experiences of others, or a combination of both.

Miriam Cates has been criticised for using the term ‘cultural Marxism’ at the National Conservatism conference. (Twitter/@NatConTalk)

The reaction to their comments was one of outrage by a great many people. As soon as binary worldviews start to influence the thinking and rhetoric of politicians, people feel pushed into ‘camps’ on one side or the other and react strongly against such over-simplification. It may be coming from a binary worldview of ‘oppressors’ vs. ‘the oppressed’ and the projection of everyone into one group or the other in almost every situation, however complex. Or it may be coming from a conspiracy theory that ‘who we are’ is coming under threat from immigration and diversity (as if ‘who we are’ in Britain could ever be identified as a static and clear concept). What are they instinctively seeking to gain from these simplistic narratives and conspiracy theories? The answer is almost certainly a sense of belonging, and an understanding of the world that is void of the cognitive stress caused by a plurality of identities and perspectives. We should also be mindful of the structural inequalities and racism that exist in our society; the level of backlash both on social media, the mainstream media and from fellow politicians for Abbott's letter outweighed that which Cates received, which also tells us part of this story.

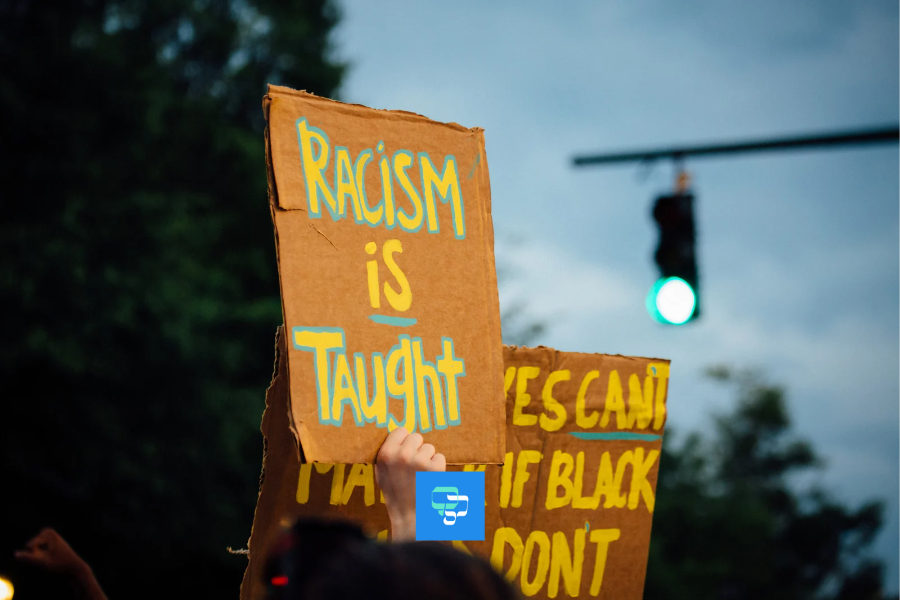

In order to deal with this, rather than be shamed into compliance through a coercive framework of rules around racism, we need to be transformed as a society so that we authentically live out counter-racism through increased knowledge and lived experience.

We can ensure we don’t make the same mistakes by doing the following:

- Be consistent with our understanding of and application of hate crime laws, and principles such as MacPherson

- Build real world educational opportunities to develop our understanding of racism and intersectionality in a way that includes different minority experiences, which has too often failed to include Jews, Travellers and others.

- Build solidarity that challenges the majoritarian and systematic discrimination that still exists in society, in our politics, our workplaces and social spaces

What might this look like if teachers want to encourage young people towards transformative experiences? Consider recommending to your students the following:

- Seek out friendships and invest effort in forming relationships with people from various different minority groups

- Reject simplistic binary worldviews that might lead you to pigeon-hole whole groups of people based on which side of the ‘right/wrong’ dichotomy you try to force them into

- Resolve to respond in a positive way to any constructive criticism that may indicate you have a bias against a particular group, rather than becoming defensive and denying it

- Don’t assume that expressions of hurt must be coming from a conspiracy to achieve a political agenda. Genuinely listen to the other side’s perspective first

- If you have caused hurt, apologise with sincere sympathy for the hurt others are feeling. Make this more important that your own need to save face for having made a mistake

- Use process rather than static statements when addressing racism. For example, say: ‘he made a racist comment’, rather than: ‘he is a racist’

- Research tropes and stereotypes associated with various different people groups so that you can look out for them and avoid them

- Research beliefs and practices of other faiths and cultures so that you can understand them and communicate better with others

- Get training in nonviolent communication techniques - you are more likely to achieve a better outcome if you use such techniques

- Instead of trying to promote your own victimhood above others, seek to understand others’ stories of suffering in order to build solidarity towards a cause that sees all racism and prejudice as equally bad, and that seeks to establish individual human rights and equality for all

Ultimately, we need to keep in mind the ideal of a fair and compassionate society where we celebrate diversity and protect one another from harm. What ‘group’ we are perceived to be from should not change our equal stake in that ideal, nor our responsibility to strive to make it a reality.