“You and I inhabit a land that is, conceptually at least, two lands. Between the river and the sea lie the land of Israel and the land of Palestine. Tragically, those two entities happen to exist in the same space”.

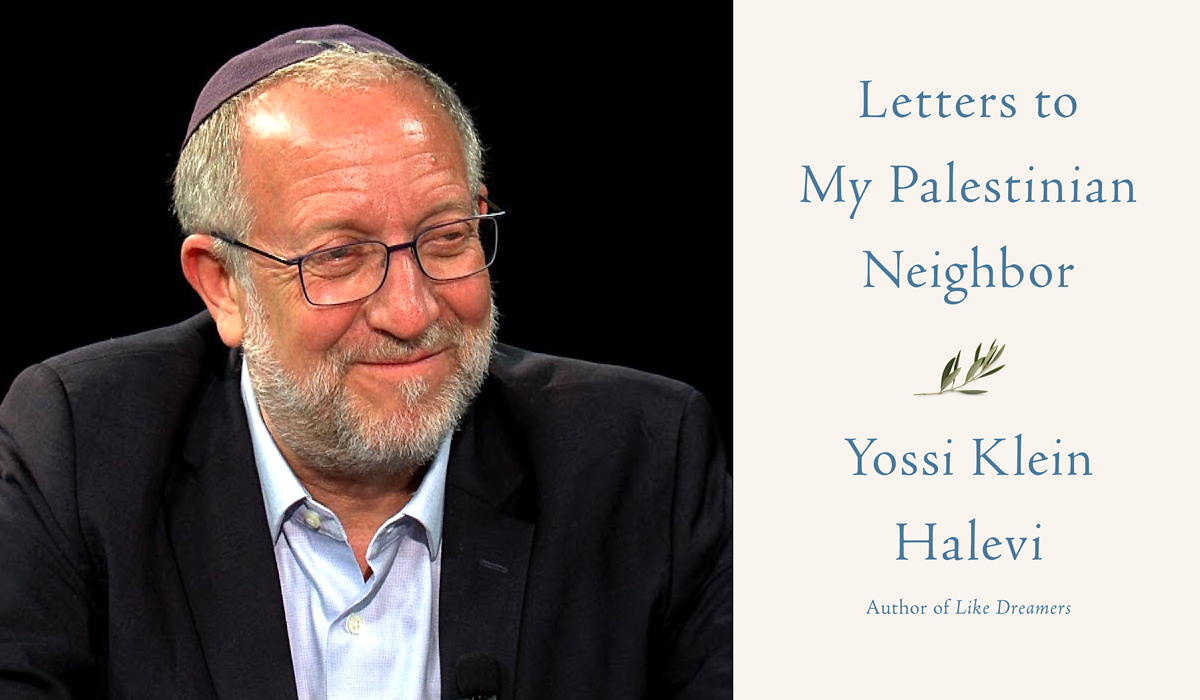

Yossi Klein Halevi is not a typical Israeli peace activist. In his youth he was a self-confessed ‘Jewish extremist’, and he was inspired by Israel’s victory in the 1967 War to leave his home in the US and take up residence in the newly occupied West Bank. Nowadays, still deeply religious, he identifies as being in the political centre and sees the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel as a historical necessity.

Through his new book, ‘Letters to my Palestinian Neighbor’, the author seeks to initiate a more profound dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians. The book takes the form of a series of letters, each dealing with a topic of fundamental importance to the self-understanding of Israeli Jews - such as peoplehood, trauma and historical connection to the land.

Halevi does not disguise his intention with the book, which he introduces as ‘an attempt to explain the Jewish story and the significance of Israel in Jewish identity to Palestinians who are my next-door neighbors’. Clearly, the author is not the first to try to explain Zionism to an external audience (be it Palestinian or international) and he won’t be the last; after all, this has been the premise of Israeli hasbara [literally ‘explaining’] for decades.

What the author recognises, however, is that the Jewish-Israeli and Arab- Palestinian historical narratives, as they are usually told, almost intrinsically serve to deny each other’s legitimacy in order to demonstrate their own righteousness. Rejecting outright this zero-sum approach, Halevi seeks instead to leave space for the Palestinian narrative to exist alongside his Israeli narrative, both metaphorically and literally: in the book’s paperback version he devotes an extended epilogue to Palestinian responses to the book (both supportive and critical).

“Some Jews continue to try to ‘prove’ that Palestinian national identity is a fiction, that you are a contrived people,” he writes. “Of course you are - and so are we. All national identities are, by definition, contrived.” Ultimately, he argues, “accommodating both our narratives, learning to live with two contradictory stories, is the only way to deny the past a veto over the future.”

Clarifying that he is not seeking to convert Palestinians into Zionists, Halevi argues: “Neither of us is likely to convince the other of each side’s narrative. Each of us lives within a story so deeply rooted in our being, so defining of our collective and personal existence, that forfeiting our respective narratives would be a betrayal.” His motivation for writing the book, therefore, is different: “I don’t believe that peace without at least some attempt at mutual understanding can endure. Whatever official document may be signed by our leaders in the future will be undermined on the ground” - as, it could be argued, were the Oslo Accords of the 1990s.

Halevi is beautifully articulate, and has a unique ability to frame old concepts in refreshingly new ways. With that said, he doesn’t always succeed in achieving his aim of according legitimacy to the other narrative, at times reinforcing the very tropes that he purports to avoid. He is called out on these in several of the response letters in the epilogue, and it is to the writer’s credit that he leaves himself publicly open to such critiques.

For example, one responder takes issue with Halevi’s assertion that “Palestinian refugees are the only refugee community in the world whose homeless status is hereditary.” The anonymous responder first corrects the statement - “children born in UNHCR camps [...] are counted as refugees too” - before flipping the argument on its head: “The correct statement is that Palestinians are the only modern group of refugees still in existence whose right of return has been denied for multiple generations.”

In another response (printed in the New York Times but unfortunately not included in the book’s epilogue for copyright reasons), Palestinian lawyer and writer Raja Shehadeh picks up on another historical fallacy which Halevi reproduces: “the suggestion that the land of Palestine was empty before Zionists arrived”. Albeit less explicit than the traditional ‘land without a people for a people without a land’ formulation, the author’s use of these and other tropes nonetheless betrays what are perhaps some of the leftover motifs from his more right-wing years.

Despite these shortcomings, ‘Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor’ is still an admirable endeavour, the importance of which extends far beyond the book itself. Since its publication, Halevi has carried the book’s message into real- life dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians and continues to be active in seeking to enhance both people’s understandings of the other.

Halevi has written only one side of a dialogue that needs to be truly bilateral if it is to bear fruit, and he could do more to acknowledge the power imbalance between both peoples. But his openness to the other side and his desire to make that dialogue a reality is something we can all learn from.

You can find Ben here. You can buy the book from Hive.co.uk here. SNS does not benefit in any way from this recommendation. If you’d like to support us please consider making a donation.